Black holes are among the most studied but least understood cosmic phenomena for astrophysicists. While not technically a “hole,” these objects derive their name from the fact that nothing, including light, can escape the grasp of their immense gravitational field. While black holes do not emit light of their own, any gas in their immediate vicinity gets very hot and luminous as it spirals into the event horizon – the distance from the hole at which the gravitational field is so immense that light cannot escape – and this gas can be episodically supplied when a black hole feeds on a star.

When a star comes sufficiently close to a supermassive black hole (SMBH) it is pulled apart. Some of the tidally destroyed material falls into the black hole, creating a very hot, very bright disk of material called an accretion disk before it plunges through the horizon. This process, known as a tidal disruption event (TDE), provides a light source that can be viewed with powerful telescopes and analyzed by scientists.

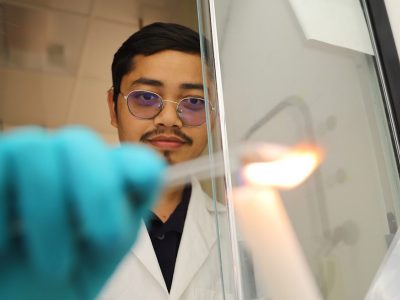

Among the physicists who study TDEs to learn more about SMBHs is Eric Coughlin, a professor in the College of Arts and Sciences. He was part of a seminal study in 2023 with Dheeraj R. “DJ” Pasham, a research scientist at MIT, and Thomas Wevers, who at the time was a Fellow of the European Southern Observatory. They proposed a model for a repeating partial TDE, which is when a star is captured by a SMBH, but instead of being completely destroyed, the high-density core of the star survives, allowing it to orbit the black hole more than once. Their results were the first to use a detailed model to map a star’s surprising return orbit about a supermassive black hole—revealing new information about one of the cosmos’ most extreme environments.

Coughlin, a physicist, was involved in understanding the properties of the accretion flow that formed around the black hole during this TDE, the radius and mass of the star, and the mass and spin of the SMBH. Because the spin of black holes can be modified by how they accrete from their environment, Coughlin notes that this study fills in another piece of the puzzle when it comes to understanding the evolution and behavior of black holes. For example, if many of the black holes in the universe are spinning very rapidly, it suggests that material is consistently funneled onto a black hole from the same direction over cosmological timescales. If, on the other hand, black holes are not all rapidly rotating (or very few are), then it suggests that black holes grow intermittently and in a sporadic way.

“Which one of these processes occurs is tied to galaxy formation and evolution, and hence measuring black hole spin indirectly tells us about the gas-dynamical properties of galaxies and the universe on large scales,” Coughlin says of this study, which paves the way for high-cadence monitoring (when many observations are taken in a short amount of time) to have the potential to reveal fundamental properties of black holes if they can be detected early on.

“New technology like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will allow us to probe deeper into the universe than ever before. We hope that this study offers justification for rapid X-ray follow-up of more tidal disruption events. If we can achieve this, then ideally, we can start to probe the spins of black holes through tidal disruption events.”

This research was funded, in part, by NASA and the European Space Agency.

Read the full story on the Arts and Sciences website.