Lender Center Researcher Studies Veterans’ Post-Service Lives, Global Conflict Dynamics

Corri Zoli ’91, G’93, G’04 was recently named a research associate of the Lender Center for Social Justice. She applies social science, law and public policy perspectives to problems of warfare, governance in modern human conflicts and the role of international humanitarian law in managing conflict dynamics.

Zoli’s Lender Center project looks at how veterans navigate post-service life, how marginalized communities are impacted by conflict and how public policies can be made more fair, inclusive and humane. “National security is often framed in abstract or geopolitical terms, but it’s essentially about people and whose lives are protected, whose voices are heard and whose rights are upheld. I try to humanize conflict and security,” she says.

We spoke with Zoli about the impact her research has for veterans and in matters of national security and public safety.

How does being at Syracuse University support and enhance your work?

Syracuse University has longstanding commitments to public affairs, community engagement and military veterans, and a unique history that started with Chancellor [William] Tolley throwing open the doors to returning GIs following World War II. This private university has since become one of the most welcoming places in the country for veterans. Tolley was visionary—I think he knew veterans would transform the campus by sharing their knowledge and experiences, and they did. We say we have it in our DNA to support veterans, and it’s true. The National Veterans Resource Center and D’Aniello Institute for Veterans and Military Families have put that into practice.

But the commitment is deeper. Lots of universities work on retraining veterans or on public affairs, but here, we ask fundamental questions about public service. We’re willing to go the extra mile to support the communities that are part of that research. We ask what can we all do together and how can we advance knowledge through community partnerships. We put effort and resources into what we can learn from veterans’ service and skills.

Similarly, the Lender Center recognizes that the university is best when it is grounded in its communities and its work is a two-way street. We’re not just gathering data, we’re welcoming community members as stakeholders and contributing partners. It’s wonderful to join so many Lender colleagues and students from across the University who share a passion for community, partnerships and the real-world impacts of our research.

Much of the research supported by the Lender Center is focused on the wealth gap in America. How does your work on veterans connect to that?

We are finding that military service is a unique way to mitigate the wealth gap and many socioeconomic gaps. Thirty years of economic data on veterans and service members shows that other things being equal, veterans have a wage premium, so military service can be a way to increase your socioeconomic advantage in the U.S. It means that anyone who is underserved and/or economically disadvantaged without other opportunities may want to consider a military career or national public service.

What is a key takeaway from your study of veterans’ post-service experiences adapting to non-military life?

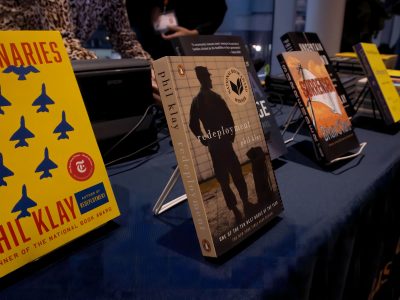

While the U.S. public overwhelmingly supports veterans, we don’t really know them or their stories. We thank them for their service, but it’s otherwise superficial; it’s not like World War II, where everyone knew a veteran. We’re asking, “How do we as a country put effort and resources into getting to know the veterans in our midst, then tap their knowledge and feedback?”

How can veterans inform our approach to conflicts, security and safety?

Veterans have on-the-ground knowledge about how to address conflict and its root causes. They can provide strategic advice, but we don’t use them enough as resources for applied practical expertise. Post-9/11 vets can offer important feedback on issues of national and global security and military challenges, and on topics such as infrastructure development, given the many roads and buildings the U.S. built in Afghanistan and elsewhere. We would do well to get their input on government policies, public safety, modernizing and innovating our technologies, infrastructure development and building higher educational programs more inclusive of veterans.

What are some core findings from your research on national security?

Conflicts are much more complicated now than in the past, and many involve unconventional warfare—new cyber weapons and drones, violent or political extremism and the creation and support of terrorist organizations below the state level by actors who are not responsive to their governments.

We lack policy tools to really fight these conflicts well. Our inability to manage the explosion of non-state conflict actors, for instance, creates enormous civilian harm and pockets of instability or ungoverned zones in many regions of the world. We can’t control international spaces, but we can offer support and best practices and make sure our own national laws and policies are consistent with and follow civil liberties norms and our constitution.

What does your research reveal about issues of public safety?

We need to do a bit more than we’re doing in terms of domestic safety and involve communities more in their own safety and security. We need to beef up infrastructure that protects public safety, including keeping roads and bridges and other infrastructure in good shape. We should be educating students at the K-12 levels in how they can play a role in public service and public safety and to consider public safety careers. We should make civic engagement and understanding, including our constitutional traditions and standards, well known to everybody.